Risk of Ruin, Expected Returns

By: Russell Sands

The following is an excerpt from Russell Sands' Turtle Secrets

Risk of Ruin

Risk of Ruin is a very important subject. Ruin is defined as when a trader does not have enough capital left to trade in the markets. For an individual, this usually means losing all of your money, or not having enough left. For a corporate trader, it means losing enough money for your firm so that you get fired. And for a money manager, it is losing so much for your clients that they close their accounts.

While risk of ruin is extremely important, it is too often ignored by most people. There are two reasons for this, but neither of them is very good. The first is that people are scared by the sometimes higher level of mathematics involved. My answer to this is not to worry about the specific equations, as long as you can understand the basic principles and the practical meanings behind those equations. Understanding the concepts is much more important (and useful) than memorizing the rules. The second reason is even worse - spending too much time looking for the holy grail of entry signals in order to make all your trades winners, while naively ignoring the fact that losing is just as much a part of the game (if not more so) than winning. Even traders with superior or proven systems should understand risk of ruin so as to be prepared for the inevitable adverse sequences that can come along from time to time.

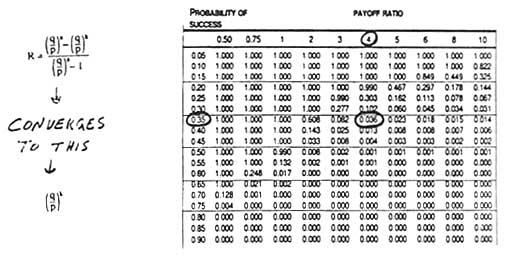

The equation given below, first formulated by the mathematician William Feller, tells us that risk of ruin is simply a function of two variables. The first is your rate of success and the second is the size of your bet. And that’s all there is to it. In this example, ‘p’ is your probability of success, ‘q’ is your rate of failure (1-p), ‘k’ is the amount of money you risk on each trade, and ‘a’ is the size of your opponent’s bankroll (the market). Because the size of the market (a) is assumed to be infinitely large, at least relative to any individual trader, the equation simplifies as several terms converge to zero.

Note that in the simple form, your risk of ruin is directly proportional to the amount of money that you risk on each trade. The more you bet, the greater your risk of ruin. This makes perfect sense, if you bet half your bankroll on a given trade, then you only have to be wrong twice in a row and you’re wiped out. But if you only risk 10% of your capital on each trade, then you have to be wrong ten times in a row in order to bust out, a much less likely occurrence. Also, note that risk of ruin is inversely proportional to probability of success, the higher your probability of success on each trade, the lower is your overall risk of ruin.

So far the discussion has made the highly simplifying assumption that the payoff is even money. When this is not the case, as in the Turtle trading systems, the mathematics get complicated beyond the scope of this author (i.e. I don’t understand the equations either). In our trading, we aim for a payoff, when we are correct, of three or four times the amount of money we are willing to risk if we’re wrong. We have to do this because our trend following style will produce winning trades less than fifty percent of the time. So common sense says that if you are going to lose more often than you are going to win, then the winners have to be larger in size than the losers in order to come out ahead in the long run.

Before counting how much we can make from the markets when we’re right, however, we must first focus on controlling the losses and the downside of trading. The absolutely worst thing that can happen to a trader is to suffer through a string of losses due to an adverse period in the markets, and then not have enough money left to trade when the good times come around. It is therefore crucial to have an understanding of risk of ruin so that you can determine how much to risk on each trade for your given risk utility level of tolerance or loss.

The table below appeared in an issue of Technical Analysis of Stocks and Commodities, and was produced through simulation techniques by a trader and mathematician named Nauzer Balsara. Payoff ratios are listed along the top, success probabilities are down the left hand column, and the numbers within the matrix represent risk of ruin probabilities. Balsara says this table was constructed with the assumption that 10% of your bankroll is risked on each individual trade, a number that is way too high for me, but may be necessary to those with very small trading accounts. Please remember that over-trading, while bad, is not necessarily ‘wrong’ as long as you understand that larger size trading incurs a higher risk of ruin. Each person must decide for himself what level of risk to incur, whether trading for a hobby or as a business.

Expected Returns

The flip side of Risk and Ruin is Expected Return. The trick, of course, is to find a trading methodology, as well as a trading size, which will allow you to earn a decent return on your capital while at the same time holding the Risk of Ruin to an acceptable level. There is no magic here, and the common sense axiom holds true, the more you are willing to risk, the more you should earn; if you can accept a lower return, then you have to risk less. The risk/reward ratio for Turtle trading should be on the order of three to one. The only thing that differs is the magnitude, based on your individual utility curve. If you can stand a thirty percent loss, you can make a hundred percent a year. If you are happy with a thirty percent return, then you only need to risk ten percent of your capital. Of course, it isn’t always this easy in real life, but this is the way the mathematics should work out.

The first question we have to ask is how to have a positive long run expectation (i.e. make a profit) if we lose on two thirds of our trades. The answer lies in the fact that Expected Return is made up of two components, the probability of winning on any give trade and the size of the win (relative to the size of the loss). Mathematically, we can say that E (R) = (p x P) – (q x L), where “p” is the probability of winning (a fraction between 0 and 1). “P” is the size of the win (in Units), “q” is the probability of losing (also equal to 1-p), and “L” is the size of the loss.

The table below is constructed with each scenario (A-D) having an equal probability (50%) of winning or losing. In case A, with a 50/50 win loss %, and even money payoff (win one unit or lose one unit), the Expected Return is zero. This means that no matter how long you play or how often you bet, in the long run you should come out exactly even, not winning or losing. However, while the Expected Return in this case is zero, the Risk of Ruin is almost a certainty. The reason for this is that if you play long enough, and assuming that your opponent (the market) has infinitely more capital than you, there will eventually be an adverse sequence of events that will wipe you out in the short run, before you have the chance to get into the long run. The moral of the story is that it is very bad to play an ‘even money’ game.

Case |

p |

P |

L |

E(play) |

%Ruin |

A |

1/2 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

100% |

B |

1/2 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

0-2% |

C |

1/2 |

6 |

2 |

2 |

5% |

D |

1/2 |

9 |

3 |

3 |

13% |

However, in case B, where the payoff is three times as much when you win as when you lose, your long run expectation will be one unit. If you make two bets in this game, one time you win 3 points, and the other time you lose 1 point. That’s a net gain of two points. Divided by two bets, that’s an expectation of one point (per play). This is such a favorable game, that if you played small enough relative to your bankroll, you would have less than a one percent chance of going broke. The moral of this story is that if your wins are larger than your losses, and you win half the time, you will make a lot of money in the long run.

In cases C and D, all you are doing is increasing the size of your bet (the leverage), but keeping the win/loss ratio the same (3:1). Therefore, your Expected Return increases proportionately to the leverage employed in the betting size. But, one of the worst things that you can do is over-trade (over bet). Risk of Ruin increases exponentially once you start betting or trading larger than your money management scheme says you should.